I work and they get richer.

You work and they get richer.

We all work harder and the few get richer.

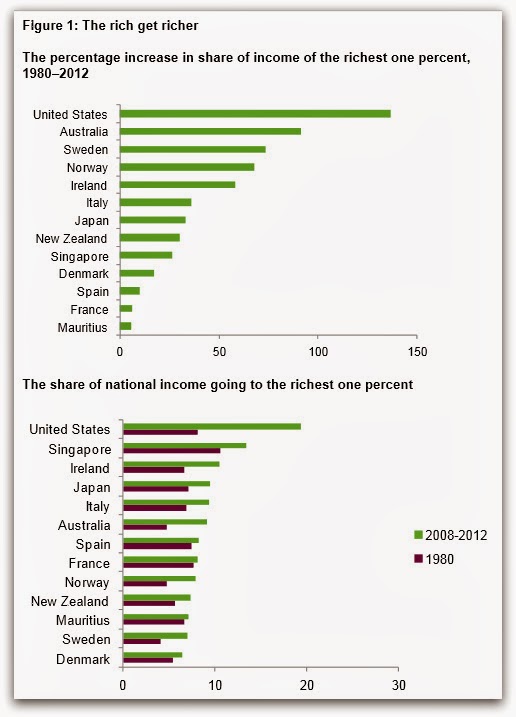

Average income has been flat for decades; the income of the wealthy has increased radically. (The wealthiest 1% captured 95% of post-financial crisis growth since 2009 while the bottom 90% became poorer.)

We all work harder so they can get richer.

Is that actually what is happening?

In 1988, the income of an average American taxpayer was $33,400, adjusted for inflation. Fast forward 20 years, and not much had changed: The average income was still just $33,000 in 2008, according to IRS data. Keep in mind that that's an average, and the rich are getting richer at a tremendous rate during that period.

"In many countries, extreme economic inequality is worrying because of the pernicious impact that wealth concentrations can have on equal political representation. When wealth captures government policymaking, the rules bend to favor the rich, often to the detriment of everyone else. The consequences include the erosion of democratic governance, the pulling apart of social cohesion, and the vanishing of equal opportunities for all. Unless bold political solutions are instituted to curb the influence of wealth on politics, governments will work for the interests of the rich, while economic and political inequalities continue to rise. As US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis famously said, ‘We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of the few, but we cannot have both.’"

The subject is called economic inequality or the gap between rich and poor. There are opinions, but in general, the greater the gap, the greater the nation's difficulty with economic growth, governmental and marketplace corruption, foreign investment, and foreign debt. The byproduct of the gap can also be measured in human distress and the struggle for survival.

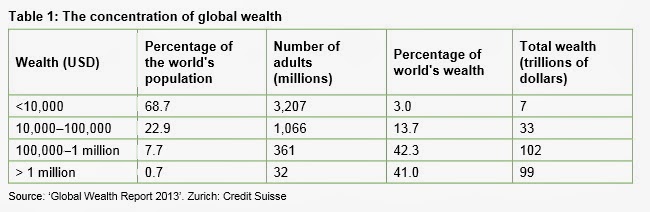

Note in the table (right) that the percentage of income going to the rich has increased, but it varies among nations. It suggests the income available to share among the rest is reduced, again with variations.

The bigger the gap ... so what? Does it change things? There are differing opinions among economists regarding the cause and effect analysis.

A summary, "The U.S. economic and social model is associated with substantial levels of social exclusion, including high levels of income inequality, high relative and absolute poverty rates, poor and unequal educational outcomes, poor health outcomes, and high rates of crime and incarceration. At the same time, the available evidence provides little support for the view that U.S.-style labor-market flexibility dramatically improves labor-market outcomes. Despite popular prejudices to the contrary, the U.S. economy consistently affords a lower level of economic mobility than all the continental European countries for which data is available."[REF]

The bottom line? When the rich get richer, it has to come from somewhere.

In the short view, wealth comes from labor, innovation, creativity, cooperation, collaboration, risk-taking ... but as the gap widens, those things become progressively less significant. The wealthy are disproportionately represented in government policies and marketplace advantages.

I sat with friends (who work much harder than I do) around a home fire on home-made stools in a western African village while they explained to me all the things they were doing, hoping to provide for their families. They aggressively pursue every opportunity to "do a little business". In a very good year, they generate around $1500 for their household. Normally, it's less. The impediments to their progress, an exclusive upper class and a government that's crooked as a dog's hind leg.

(It's different here in the developed world, of course.

Isn't it? Of course it is. It must be. It must.)

It's particularly troubling when the widening gap points to differences in mortality, available nutrition, access to education, to basic healthcare and safe neighborhoods. Historically, such a gap often precedes significant upheaval, both national and international. At some point, the laborer will no longer work and sacrifice his life and the lives of his children for the benefit of another's opulence and privilege.

Thoughts?

The top of the economic pyramid is not the moral high ground. The only way for a small group of people to become obscenely rich is for huge masses of others to be kept quite poor.